“Book of Kells”

by Jerry B. Lincecum

[Note: This article appeared in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram

on March 29, 1990]

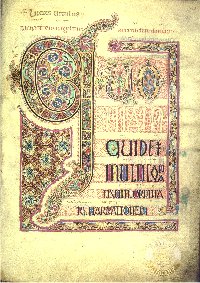

Ireland's famed “Book of Kells,” the Western world's most beautiful

illuminated manuscript, is also one of our greatest riddles.

Now, thanks to a superb fine art facsimile edition, scholars

and students at Texas Christian University and Austin College

can study it from cover to cover in search of new answers. Trinity College in Dublin also provides a website.

One copy of the expensive facsimile edition, valued at $18,000

per book and limited to 1,480 copies worldwide, was presented

to Austin College in Sherman last night. Another goes to the

Texas Christian University library in special ceremonies tonight.

Since the Austin College copy arrived early (two days before

St. Patrick's Day!), I have had the privilege of poring over

this gorgeous and sacred book. As for the riddles of its origin,

I began puzzling over those even before my first visit to Trinity

College in Dublin to view the original in 1970.

As best we can determine, the Book of Kells was copied by

hand and illuminated by monks around the year 800 A.D. Although

it was probably begun on the island of Iona, between Scotland

and Ireland, its name is derived from the Abbey of Kells, in

the Irish Midlands, where it was kept from at least the 9th century

to 1541. One theory has it that portions of the book were made

at Kells, after Viking raids on Iona forced the monastery to

retreat to the more isolated location, is uncertain.

The book consists of a Latin text of the four Gospels, calligraphed

in ornate script and lavishly illustrated in as many as ten colors.

Only two of its 680 pages are without color. Not intended for

daily use or study, it was a sacred work of art to appear on

the altar for very special occasions.

Since 1661 the Book of Kells has been kept in the Library

of Trinity College in Dublin. The fact that the preservation

of medieval manuscripts requires strict conservation measures

was not understood in the 19th century and the book suffered

from more than the ravages of time. It suffered damage when it

was improperly rebound in ?. Not recognizing that some of the

pages varied in size, the binder actually cut off some of the

gorgeous illumination in order to standardize the size.

In 1953 the book had to undergo a major process of restoration.

At that time it was rebound into four volumes, permitting greater

access. In Dublin two volumes of the Book are displayed daily

under strictly controlled conditions, while the other two are

available to a few privileged scholars. Pages are turned on a

regular schedule to allow the public to view different sections

of the book. Thousands flock to Trinity College annually to view

this sacred book that is also the finest surviving example of

the art of illumination and Celtic art.

To make this treasure more accessible, officials at Trinity

College decided in 1986 to allow a limited number of high quality

facsimiles to be made by a Swiss publisher, Urs Duggelin, whose

firm (Faksimile Verlag or Fine Art Facsimile Publishers) specializes

in reproduction of rare illuminated manuscripts and has an outstanding

reputation. Duggelin considers this project the fulfillment of

a lifetime dream, but when he first proposed it, officials at

Trinity College said no, unequivocally.

But when he offered to observe unusually strict security and

preservation measures, the door opened. The original was not

to be removed from Dublin. It could not be unbound (usual practice

for photo reproduction), and worst of all, its pages were not

to be touched by anyone or anything--not even a glass photographic

plate.

Undeterred, Duggelin invested a quarter of a million Swiss

francs and two and a half years of work to invent a unique machine

that allowed them to photograph the book without touching it.

The photography was done over several days in August 1986.

Then the real work began. Master lithographers and craftsmen

drew upon computer enhancement as well as their own skill to

reproduce a true facsimile (the latin word means "Make it

the same!"). Each page traveled an average of five times

between Ireland and Switzerland.

The copy recreates faithfully the present-day condition of

the original, including some 580 holes made by beetles, weevils,

and the aging process. Normal color printing is limited to four

colors, but some pages of the Book of Kells had ten colors, so

a more complicated and costly process was followed. The books

are bound and sewn by hand, following a medieval process that

requires great skill.

What do we know about the artists and craftsmen who made the

original, almost 1200 years ago? Not very much. No records have

come down to us. There is no list of credits, not even an account

book. There are some visual clues, however. Experts who have

studied the manuscript have been able to identify only four "hands"

in the calligraphy. But medieval artists were known to use themselves

as models on occasion, and one scholar has posited the theory

that the nine apostles who are depicted on page 202 just might

be the book's creators.

Four were master-painters and calligraphers. The other five

would have kept busy preparing the pages, mixing colors, making

tea, and (when their masters backs were turned) taking us the

brush and having fund. No doubt some of the amusing little animals

and birds that the book is famous for were done by apprentices.

The masters must have been short-sighted, because only when

a 10-factor magnifying glass is applied to the figure of St.

Luke on page 201 does one see the breathtakingly intricate and

exact decoration. There are numerous other examples of this kind

of fine detail, and magnifying glasses of that power were not

invented until hundreds of years later.

Two of the painters stand out by virtue of their genius and

their contrasting style. One was Celtic (either Irish or Scottish).

He was exact, orderly and neat, always using black ink made of

iron-gall. His exquisite writing alone would make the book a

masterpiece. His colors are blue and green. Toward the end of

the book are two of his pages, with blue letters on one and the

complementary green on the other.

His greatest rival must have been a southerner--an Arab, an

Armenian, or an Italian. He knew the art of the Mediterranean

world and painted in a style that is bold, even fantastic, and

a perfect foil the swirling gracefulness of Celtic art. He will

start a section of text in black, throw in a chunk of scandalous

scarlet, shift into brown, then return to black. He is forever

throwing in wilful little details--sprigs of wild flowers, eccentric

dots and diamonds. His is certainly the greatest page of the

Book of Kells, the fabulous "Chi Rho" page (so called

after the Greek initial letters of Christ's name).

There are enough puzzles and conundrums in this masterpiece,

not to mention splendid images and awe-inspiring calligraphy,

to intrigue students and scholars at Austin College and Texas

Christian University for years to come.

These images are from the Book of Kells Images.

Similar art can be found in the Lindisfarne

Gospels. Similar art can be found in the Lindisfarne

Gospels.

The Lindisfarne Gospels are one of the treasures

of the Christian Church in Northumbria. They were produced in

the 7th century at a time which is sometimes called the "Golden

Age of Northumbria" when learning and artistic skills were

at a peak. This was the age in which the Venerable Bede wrote

his "Ecclesiastical History" and in which the great

Celtic Saints like Aidan and Cuthbert carried out their missionary

work for the conversion of the North.

The Lindisfarne Gospels are currently in the care of the British

Library, in London, but the Diocese of Durham hosts some high

quality images from sample pages of the gospels. Click on the

thumbnail images to fetch the full size version.

Back to Beowulf

or Assignments or Home.

|