Why Can’t They Get Irene Adler Right? |

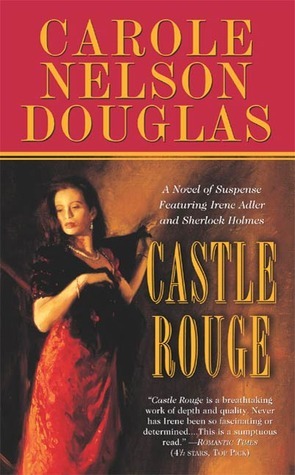

That 1990 debut novel, Good Night, Mr. Holmes, was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Seven more novels followed, and now, the first four are newly available as ebooks. To Sherlock Holmes, Irene Adler “is always the woman..... In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex.” So Dr. Watson introduced Adler in the first Holmes short story Sir Arthur Conan Doyle To me, who’d read and reread the Holmes stories at a young age, the Irene Adler depicted in Sherlockian films and books was an unsatisfying stereotype, a “Victorian vamp.” She was not only a shady lady, but dead on arrival. And this was “the only woman” to outwit Holmes? So, after spotting yet another male-centered Holmes spin-off series, I searched the Canon for a heroine and, unsatisfied, reluctantly reread “A Scandal in Bohemia.” I met again the gutsy, empathic, and clever woman whom Holmes respected, with her “resolute mind” and “inviolate word,” a female character strong enough to match the larger-than-life dimensions of the genius detective.

To later interpreters—all men—Irene is the beautiful, sexy ex-mistress of a besotted king, an apparent blackmailer. Yet she wants only to elude her victim. After successfully evading six of the king’s “best agents,” she then eludes both Holmes and the King once the Bohemian monarch sets the London detective on her trail. She is no one’s mistress but her own, and marries “a better man” than the king. I kept her happily married, not wanting her in a romantic story line, as women protagonists So I welcomed 21st-century film versions reimagining Holmes that—hallelujah!—included Irene Adler. Yet Conan Doyle’s 1888 creation is far more liberated (and in my recreation, even more so) than the Irene Adler of modern male writer-directors. Gone is the supposition that Holmes never would consummate anything more than a case, so Irene Adler becomes the nearest romantic object, always sexy and duplicitous and, darn, always in need of rescuing at the end. Robert Downey, Jr.’s 2009 depiction of Sherlock Holmes in a steampunky 19th-century London features Rachel McAdams’ Irene Adler, perky in her unconvincingly pert male attire. As Holmes’ larcenous ex-lover forced to work for Holmes’ archenemy, Moriarty, she pistol-whips and shoots, but she doesn’t even make the second film.

I’ve gotten emails that decry “always sexualizing and criminalizing” Irene Adler, distorting one of literature’s few triumphantly strong women into a loser. In Moffat’s world, Irene Adler (played by Lara Pulver) only “beats” Sherlock Holmes with a tool of her trade, a riding crop. It’s very ’50s naughty and glib, but betrays the woman’s potential again. The final beheading scene—stretched to the very last moment—is a castration-like threat for a woman who says “brainy is the new sexy.” Off with her head, then! In May, CBS’ hit Elementary series, featuring the very model of a modern 12-step Holmes (Jonny So the 1984 Jeremy Brett/Gayle Hunnicutt PBS version of “Scandal” remains the gold standard with an Adler both classy and clever, although that Irene would never get on Jack the Ripper’s trail, as mine does. As Michael Collings wrote so eloquently of my Another Scandal in Bohemia in Mystery Scene in 1994: “The private and public escapades of Irene Adler Norton [are] as erratic and unexpected and brilliant as the character herself.... Here is Sherlock Holmes in skirts, but as a detective with an artistic temperament and the passion to match, with the intellect to penetrate to the heart of a crime and the heart to show compassion for the intellect behind it.” This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Summer Issue #130.

|

Back to Assignments or Home. |

I asked that same question in 1987 and unwittingly became the first author to make a woman from the Canon the protagonist of her own mystery series, and the first woman to openly write Sherlockian spin-off fiction.

I asked that same question in 1987 and unwittingly became the first author to make a woman from the Canon the protagonist of her own mystery series, and the first woman to openly write Sherlockian spin-off fiction. wrote, “A Scandal in Bohemia.”

wrote, “A Scandal in Bohemia.” I re-created her as the obverse of Holmes: a musician by profession who moonlights as a private enquiry agent. She honors her talent too much to sleep her way up; it took years of training to don 60-pound costumes and sing for hours in European opera houses, sans microphone. Conan Doyle made her a “prima donna contralto.” No such animal, but I use it to explain Adler following Holmes in male dress: she would have played trouser roles and fought duels onstage.

I re-created her as the obverse of Holmes: a musician by profession who moonlights as a private enquiry agent. She honors her talent too much to sleep her way up; it took years of training to don 60-pound costumes and sing for hours in European opera houses, sans microphone. Conan Doyle made her a “prima donna contralto.” No such animal, but I use it to explain Adler following Holmes in male dress: she would have played trouser roles and fought duels onstage. usually are. Because she’s “presumed dead,” she’s lost her performing art and profession. In her detective adventures, she directs her investigations with the operatic flair she so deeply misses.

usually are. Because she’s “presumed dead,” she’s lost her performing art and profession. In her detective adventures, she directs her investigations with the operatic flair she so deeply misses. Next up: contemporary London–set Sherlock from the BBC and Dr. Who revivifier Steven Moffat. His portrayal of a brilliantly nerdish, sexually ambiguous Holmes made Benedict Cumberbatch a star, but Moffat introduces the most maddening Irene Adler yet: a lesbian dominatrix who, yes, is forced to work for Moriarty, falls for Holmes, then must be saved at the end.

Next up: contemporary London–set Sherlock from the BBC and Dr. Who revivifier Steven Moffat. His portrayal of a brilliantly nerdish, sexually ambiguous Holmes made Benedict Cumberbatch a star, but Moffat introduces the most maddening Irene Adler yet: a lesbian dominatrix who, yes, is forced to work for Moriarty, falls for Holmes, then must be saved at the end. Lee Miller) and an intriguing female Dr. Watson (Lucy Liu), had a two-hour finale about Holmes’ “lost love,” Irene Adler, murdered by archenemy Moriarty. [Spoiler Alert!] Irene not only turned up alive, she was Moriarty, “the Napoleon of crime.” Now that’s Adler strong. Yet the plot still criminalizes the character, and her affection for Holmes catches her up in the end.

Lee Miller) and an intriguing female Dr. Watson (Lucy Liu), had a two-hour finale about Holmes’ “lost love,” Irene Adler, murdered by archenemy Moriarty. [Spoiler Alert!] Irene not only turned up alive, she was Moriarty, “the Napoleon of crime.” Now that’s Adler strong. Yet the plot still criminalizes the character, and her affection for Holmes catches her up in the end.